From New York Press, September 3, 1998

Some years ago, while researching William Cowper Brann, editor of The Iconoclast, a turn-of-the-century Waco, Texas monthly, I encountered the multi-talented New York–born George Graham Rice, one of America’s most successful and unscrupulous promoter-swindlers. This resulted from a natural confusion: one of Rice’s stock market tout sheets was also named The Iconoclast.

Colonel Brann (in those days most Southern editors were addressed formally as “Colonel,” owing perhaps to the degree of violence involved in the profession of journalism in that region), was a village atheist who wrote scintillating prose, supporting his paper with an admirably profitable sideline in pornography (“They were not texts from which a minister could take his lesson,” admitted one biographer). H. L. Mencken praised him as “the Voltaire of the Staked Plains” and “the greatest writer ever born in Toadsuck, Texas.” Like Villemessant of Le Figaro, the Texan believed that if a story didn’t cause a duel or a lawsuit, it wasn’t any good. Alas, while Brann was exposing some sex scandal at Baylor University, an outraged alumnus accosted the Colonel on the street and induced his death by severe lead poisoning, having shot him several times in the back.

Unlike Brann’s, Rice’s prose is utilitarian. He described himself as “a facile man with a pen”—“When news was scarce I could write more about nothing than any man I ever met.”—but his memoirs, written before his fiftieth birthday, mingle paragraphs of audacity with pages of unreadable self-justification. The book is not as much fun as its title: My Adventures With Your Money.

Rice flourished in those last innocent decades before the Securities and Exchange Acts placed restraints on a promoter’s enthusiasms. His admirer, J. S. A. “Alphabet” MacDonald, a/k/a Colonel John R. Stingo, praised him to A. J. Liebling, not as “a thief,” or even “a truly great thief,” but as a pisseur—“an appellation,” Liebling explained, “used for objects of his highest approval, like P. T. Barnum’s Jumbo, Elbert Hubbard, William Randolph Hearst, Boss Croker, or Al Jennings, the bank robber.”

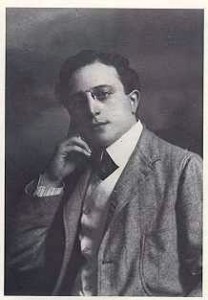

He was born Jacob Simon Herzig in 1870. Disowned by his nice middle-class family after doing time for forgery, he resurfaced under a new name in New Orleans, reporting for the Times Democrat. By coincidence, he was in Galveston, Texas during the great hurricane of September 8, 1900, when the seawall broke and the Gulf laid waste the city. Rice escaped the tidal wave, stole a horse, found a working telegraph office, and—he claimed—was among the first reporters to get out the story.

Being Rice, he double-billed his expenses, was fired, lost his money gambling, and changed careers.

It is there he begins his memoirs, writing, “The place was New York. The time was March, 1901. My age was thirty. My cash capital was $7.30. I was out of a job.” Rice began making book, doing business as Maxim & Gay. (A partnership sounded more respectable than a one-man bookie operation.) He took the first name from a machine gun and the second from a sign he’d seen in the street. Within a year, he was publishing a sprightly racing sheet, Daily America.

Touting the publisher’s own bookmaking firm for its skill and integrity in horse-picking was acceptable, almost traditional. Rice’s flaw, then and throughout his life, was lack of restraint. As bettors began wagering by the Gospel according to Rice, he began systematically manipulating the odds, day after day, by reporting, not reporting, or inventing stories about the horses, the jockeys, the stables, and the tracks was not.

His competitors lacked a sense of humor about losing money and acted against him in mysterious ways. Rice lost control of his paper to The Daily Racing Form, and was soon broke. He went west.

In 1903, men died of thirst in the desert at the place that would become Tonopah, Nevada. Two years later, Tonopah had come into booming existence as the center of the last great North American gold rush. It was overrun with miners, prospectors, gamblers, vaudeville performers, mining stock promoters, boxers, newspaper reporters, and ladies of frail virtue. Main Street was a two-thousand-foot-long strip of bars, dance halls, and gambling dens, with fandango houses (a euphemism for love store or house of carnal recreation) every fifty feet. “Water was four dollars a barrel,” Rice wrote, “and there was some talk of building a church.”

It was a fast town. Lucius Beebe wrote in Mixed Train Daily of a trigger-happy bad man who descended from a Pullman of the Tonopah & Goldfield Railroad, investigated the resources of the Nose Paint Bar, shot up the Tonopah Bank & Trust Company, and became the unwilling guest of honor at a neck-stretching party, all within three hours. Rice suggests the Bank was better robbed from within: “It was a tin bank, literally and figuratively, being constructed of corrugated tin plate with a false front, and when it went up the flume in 1907, the officers having been informal in their book-keeping, the aggregate cash balance in the safe was eighty cents.”

Rice had barely stepped down from the train when he encountered a former gambling associate who wanted to peddle shares of stock in the Tonopah Home Gold Mine. There was no mine, not even a hole in the ground. The Tonopah Home Gold Mine was merely a claim in an area near a gold strike, and the mining rights were held on a one-year lease. But the corporation had been organized and stock certificates printed up. This important factor eliminated “the delay and expense incident to preparing something for the immediate consumption of the public.”

As a mining stock promoter, Rice believed “having a market is as important as having a mine.” He established a news bureau to provide colorful stories about the mines, the miners, and the gold being found at Tonopah, and the nearby towns of Goldfield, Manhattan, Rawhide, and Bullfrog. He began wiring “reports of gold discoveries, shooting affrays, gamblers’ feuds, stampedes, hold-ups, narrow escapes, murders, and so forth. Some of them were true.”

At his most shameless, he could write a description of an ore sample from the Balloon Hill mine in Rawhide as “gold with a little rock in it,” going on to say, “When a man is broke in Rawhide, he can always eat. All he has to do is go…pan out breakfast money.” He describes concocting a story about an attempted robbery of the Tonopah Home Mine’s manager, complete with gunplay, posses, runaway horses, and dynamite explosions. He regretted only that the pressure of events prevented him from the ultimate touch: “I should have seen to it that the mine manager was actually robbed.”

Eventually, he and other promoters (Rice was not unique: merely more organized than most) even hired workers, leased mining equipment, dug shafts, and ran pumps and machinery night and day, not to search for gold, but to look busy for potential investors and visiting journalists. Just for the fun of it, he arranged a phony strike and riot, complete with torching a mine house, for the unwitting benefit of the wildly successful sex novelist Elinor Glyn, who was writing stories on the West for the Hearst papers.

He began promoting Tonopah Home at fifteen cents a share. “In my enthusiasm,” he later recalled, “I wrote stories about [the mine] which might have induced the reader to believe that when all the riches of that great treasure house were mined, gold would be demonetized.”

Tonopah Home was the first of many. Rice puffed and promoted the Four Aces, Gold Scepter, Bullfrog Gold Bar, Stray Dog, Jumping Jack, Flying Pig, Red Top, Silver Pick, Inspiration, Nevada Wonder, and dozens more, all for ten,twenty-five, or fifty cents a share. Looking back, he wrote, “It was an orgy in market manipulation and money fleecing that had no parallel in history. As a mining stock boom it was a dizzy bewildering success, full of red fire and explosions to the last curtain climax.”

For example, his syndicate purchased the Tramps Consolidated Gold Mine for $150,000 in notes; sold two million shares at fifty cents each, paying the notes from the proceeds; issued Rice and his associates 500,000 shares as a bonus and puffed the stock up to three dollars on the San Francisco Mining Exchange through dishonest publicity and wash sales, secretly buying and selling the same stock over and over again to generate artificial activity and attract investor interest. Then they unloaded. “Today,” Rice wrote in 1915, “the stock is at three cents a share and has never paid a dividend.”

Rice continued, “The Goldfield Daisy went from fifteen cents to six dollars a share. At one time, its market value was $9 million. It never earned a dime. Great Bend never even opened a mine. Yet it went from ten cents to $2.50 a share.” Pointing to a successful project, the Mohawk of Goldfield, which went from ten cents to $20 a share, Rice argued that “two hundred to one money is more than can be won on a long shot at the races and not so much less than the old Louisiana Lottery.” (Rice does not remind his reader that the old Louisiana Lottery was fixed.)

Over 2,000 mining companies were organized, raising over $200 million from investors, nearly all of which was lost. Rice said, “Far more gold was extracted from the pockets of speculators than from the Nevadan alkali. Stocks boomed up to $1.50 are now selling for five cents, others from one to three cents, and many not at all.”

By 1907, the book was dying. As one adventurer, Waymon Hogue, wrote in his 1932 autobiography, Back Yonder, “The road was full of men going to and coming from the mines. We met many who looked disappointed and dejected. We were stopped by a man wanting a match. He was a middle-aged man, carrying a bundle tied up in a red bandanna handkerchief suspended from a stick which he carried on his shoulder. Tom asked him the distance to the gold diggings.

“T’ey’s not any coldt,” he said. “T’ey toldt you a lie—a cot dam lie. You are a tam fool if you go up t’ere!”

“Wal, mister,” said Tom, “we want work. Do you thank they will give us work?”

“T’ey gif you not’ing,” he said. “T’ey got no work. T’ey got no goldt. It’s all a cot tam lie!” Saying this, he walked on.

By the late 1940s, Lucius Beebe wrote in Highball, “The big hotel at Goldfield was a haunted house, no longer did the glittering roulette wheels spin the Bank Club and the Double Eagle; the Palace and Heritage saloons were a memory and lizards sunned themselves among the cellarage debris of what had once been the glittering Montezuma Club.”

Undaunted, Rice in association with one J. L. “God Bless You” Lindsay began promoting copper mines. Some copper had reportedly been found at Greenwater, Nevada, by Charles M. Schwab’s Greenwater & Death Valley Mining Company. Rice immediately organized and promoted the Greenwater-Death Valley Consolidated Mines (similar corporate names were never a coincidence in Rice’s business), El Capitan Vindicator, Copper Queen, Crackerjack, and other mining companies.

It was all fake. There were surface copper carbonates, but no exploitable ore bodies. To Rice’s disappointment, “The boom busted when only $30 million had been paid in.” But his professional pride reasserts itself: “Greenwater: it exists no more. All mine development work ceased long ago. The ‘mines’ have been dismantled of their machinery and other equipment, and not even a lone watchman remains to point out to the desert wayfarer the spot on which was reared the monumental mining stock swindle of the century. Every dollar invested by the public was lost. The dry, hot winds of the sand-swept desert now chant their requiem.”

After all, there had been gold in Goldfield: creating the copper boom at Greenwater had been a matter of artistry.

The Copper Handbook of 1908, a copper industry almanac proudly quoted by Rice, commented on the Greenwater-Death Valley Consolidated: “Taking the lowest percentage of ore reported by the company, and the company’s own figures as to the size of its ore-bodies, the first 100 feet in depth on this wonderful property would carry up to 20,000,000 tons of refined copper, worth, at thirteen cents per pound, the comparatively trifling sum of five billion, two hundred million dollars.

“It is indeed lamentable to note that this magnificent mine, which carries, according to the company’s own statements, more copper than all the developed copper mines of the world, is idle and its present office address a mystery.”

Rice later operated bucket shops (a gambling house disguised as a brokerage firm, where customers did not buy stocks but wagered on their fluctuations) as well as promoting still more cheap mining and oil stocks. All involved shameless hype through either bogus news services or a succession of tout sheets masquerading as newspapers, such as the Rawhide Stampede, Mining Financial News, Nevada Mining News, or The Iconoclast. He was imprisoned four times on various charges, including tax evasion. When Liebling interviewed Rice in 1934, the Wayward Pressman described the swindler as a potbellied, white-haired old man with an air of injured innocence. He died in obscurity.

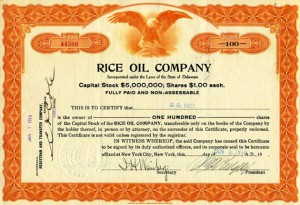

Back in 1998, R. M. Smythe & Company, then at 26 Broadway, both researched obsolescent securities and retailed old stock certificates to collectors. Whether elegantly framed or filed in the drawers, Smythe had a Golconda of old securities with the intrinsic value of wood pulp (I once wall-papered my dorm room with gaudy certificates for busted companies such as National Telephone, Middle West Utilities, and Amalgamated Copper). Amidst the sheaves of Pierce-Arrow, Packard, and Penn Central is a bright orange certificate for one hundred shares of Rice Oil Company’s common stock. Issued in 1917, signed by Rice, ornately engraved with a heroic bald eagle. At $75 this piece of paper is worth more now than at any time since Rice adventured with other men’s money.