The Code of Canon Law defines the College of Cardinals—a college in that its members are each other’s colleagues—as “the senate of the Roman Pontiff…his chief counselors and collaborators in the government of the Church.” If, as Jerrold Packard wrote, the U.S. Senate is the world’s most exclusive club, the Sacred College is a close second, and its members keep their rank for life. “Cardinal” is derived from the Latin cardo, -inis. First used in a figurative sense, the word is usually rendered in English as “hinge,” a device that, in serving as a juncture for two opposing forces, establishes harmony. Dr. J.C. Noonan Jr., in The Church Visible, his 1996 book on the Church and its protocol, suggests “pivot,” a small nail-like device, on which symbolically hangs the relationship between heaven and earth.

Their major role remains the election of a pope. Over a reign now in its third decade, John Paul II has elevated nearly all the cardinals who will elect his successor. If a mortal man can set the future course of the barque of Peter, he has. On February 21, 2001, the Holy Father elevated forty-four men to the cardinalate. The selections, though based on consultation, were his alone. At the private consistory—the ceremony at which new cardinals are formally named—the Pope asked the consent of the assembled cardinals by asking, Quid vobis videtur? (“How does this seem to you?”) The question is rhetorical: no one disagrees. At last month’s ceremony, the Holy Father handed each man the red hat of office, reminding them that it is “the distinctive sign of the Cardinal’s dignity: that even unto death and the shedding of your blood you will show yourself courageous…”

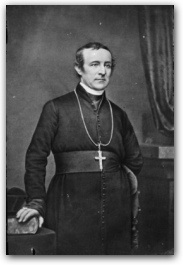

As expected, among them was Edward Egan, the new archbishop of New York. Since 1875, when John McCloskey, the second archbishop of New York, became the first American cardinal, all but one of his successors have received the red hat.

The incumbents of a few other American sees also almost automatically become princes of the Church: Baltimore, New York, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. The key word is “almost.” St. Louis has had no cardinal-archbishop in nearly a generation. John May, who was its archbishop during the 1980s, though a disastrous president of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops, somehow felt he deserved elevation to the Sacred College. The person who mattered did not share this belief. May never received the hat. Neither has his successor.

Cardinal is a rank, not an office. Thanks to Pope Urban VIII, a cardinal is styled “eminence,” a style then shared only with reigning princes. He is conversationally addressed as “Your Eminence,” more formally, as Most Eminent Lord or Most Eminent Cardinal. Describing a cardinal as a prince of the Church is no figure of speech but a statement of fact founded in international law. The Treaty of Versailles in 1919 ratified the confirmations of the Congresses of Vienna and Berlin that a cardinal held a status equal to that of a prince of the blood royal.

Cardinals still take official precedence behind only emperors, kings, and heads of state. Their relations with each other are also governed by exquisitely elaborate etiquette: even in the early 20th century, the master of ceremonies of a Roman cardinal receiving foreign cardinals had to determine the proper placement of each eminence in relation both to the host and to the door.

At the beginning, cardinals were workaday priests. Only the twelve apostles were considered possessed of full priestly powers through the commission entrusted them at the Last Supper. Their assistants, entitled deacons, were mere laymen. Cletus, the pope, recognizing a growing Church’s need for more priests (the word derives from prebyteri, “elders”), ordained 25 men to say Mass in the different Roman districts, or parishes. Some deacons and priests, who had been provided with assistants, were called cardinal deacons and cardinal priests. A third category, cardinal bishops, came into being by the ninth century. The word “cardinal” was thus an adjective, connoting a duty or assignment.

Yet each cardinal, then as now, was nominally a priest of the diocese of Rome, assigned a Roman parish. From the beginning, they elected their own bishop. As successor of St. Peter, the bishop of Rome held primacy among the bishops of the Church. When the Western Roman Empire disappeared at the end of the fifth century, the Roman pontiff became the most important office in Europe and his electors increased in worldly prestige. By the 11th century, the adjective had become a noun, conferred as a title, and the cardinals began functioning collectively as the Sacred College.

Although the Church itself is perfect, those who led it were not. With power came corruption. Cardinals came to hold vast perquisites. The office was sought for material gain rather than the service of the Church. Thus, the sons of nobles were made cardinals while still children, with little boys being dressed in clerical robes as a fulfillment of their office. The rank was even conferred on non-priests. Maurice Andrieux quoted one cardinal thus: “I know neither theology nor church history, but I know how to live in a court.”

Thus the Church came to endure the Borgia popes. Rodrigo Borgia, whose uncle, Pope Calixtus III, made him a cardinal at twenty-four, was elected pope by flagrant bribery. As Alexander VI, he granted the red hat to his bastard son, Cesare Borgia, who was neither a priest nor yet eighteen years of age. Even in the context of the Renaissance, Cesare’s conduct was somewhat unconventional for a cardinal. A poisoner and murderer, he assassinated his own brother and successfully conspired with his Pontifical father to assassinate the Duke of Bisceglie, whose marriage to Cesare’s sister, Lucrezia, was impeding her search for personal happiness.

Yet the gates of hell did not prevail. A later pope, Sixtus V, an honest and ruthless man, decreed requirements for prospective cardinals. They included a novel idea: that a cardinal be a man of blameless reputation. Sixtus also forbade anyone with children or grandchildren, living or dead, legitimate or otherwise, or who had a brother, cousin, nephew, or uncle who was already a cardinal. Our word “nepotism,” after all, comes from the Latin nepos, which means “nephew,” among other things.

Even into recent history, a Roman cardinal was expected to maintain a certain outward show of pomp, often employing at least fifty servants: chamberlains, chaplains, masters of ceremonies, lawyers, physicians, lackeys, cooks, porters, and coachmen. An enormous retinue was expected on formal public occasions: in the 18th century, Cardinal de Bernis never departed his residence without thirty-eight footmen, eight couriers, ten Swiss guards, four gentlemen, two chaplains, and eight valets-de-chambre. This did not include his coachmen, grooms and equerries on horseback. Even the shabbiest cardinal had at least three coaches—black, decorated with gilded bronze mountings—to his name. (As Lord Hervey wrote, the playthings of princes, be they ever so trifling, ought always to be gilt.)

By contrast, however, New York’s cardinals have not subjected their people to the Renaissance extravagances of the old Roman cardinals. Like most American cardinals, they were not aristocrats; they were usually quiet, hard working and incorruptible.

Finally, one other New Yorker received the red hat last month: Father Avery Dulles, a convert, decorated ex-naval officer, Jesuit, theologian, writer, and teacher. At eighty-two, he has published twenty-one books and more than 650 articles. His father, a great-uncle, and a great-grandfather were secretaries of state of the United States; an uncle was the founding administrator of the Central Intelligence Agency; yet another great-grandfather was speaker of the House of Representatives.

Dulles, born a Presbyterian, was agnostic when he entered Harvard in 1936. There his studies of Aristotle gave him confidence in human reason. Plato persuaded him of a transcendent order of right and wrong in which one has an unconditional obligation to do right, implying an absolute being to impose that obligation upon us. The Gospels reaffirmed what he had learned from the Greeks and added the idea of a loving, merciful, and forgiving God—one who had offered rescue “when we had slipped and fallen overboard,” Dulles has said. His love of the early Renaissance required him to understand its context, and thus he studied the writings of the early Church fathers, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Augustine, and Dante. It was a solitary journey: he had no close friends who were practicing Catholics, and through the exercise of his reason, he came to believe.

He converted to Catholicism in 1940, much to his father’s distress; served in the Navy during World War II, and returned after an attack of polio in Naples (its sole evidence the cane with which Dulles walks) to enter the Society of Jesus. Francis Cardinal Spellman ordained him in 1956.

Dulles has been a teacher since 1951. There is some talk that Fordham may give him a larger office. As Cardinal Dulles is more than eighty years old, he cannot vote for the next pope. Though the oldest man elevated in February 2001, as a priest he is the most junior of cardinals.

As may all princes, Dulles has taken a coat of arms. In the language of heraldry, his achievement of arms is ensigned by the red galero, the broad-brimmed cardinal’s hat from which are suspended fifteen red fiocchi, or tassels, on either side. Behind the shield is the jeweled episcopal cross and staff symbolizing his rank. Below is his motto, taken from the second letter of Timothy, scio cui credidi, “I know whom I have believed.” The shield is divided per fess, horizontally. In base, the lower half, appear the lilies of France, an example of punning heraldry, for his family believes their name was derived from the French de lys. In chief, the upper half, appears IHS, the Greek abbreviation of Jesus. There the old sailor also placed a single star. It is an attribute of St. Mary, Mother of Jesus, whom Catholics hail as Our Lady of Refuge, of Pity, of Reparation, and of Reconciliation, the Help of Christians, Queen of Peace, whom some call Star of the Sea.

New York Press, March 20, 2001