From New York Press, September 16, 1998

Elections are dull because politicians are. They can’t help it: only safe, conventional men and women with bland, plausible personalities can raise the kind of money required to pay for television commercials and bulk mailings. Authentic old-fashioned elections—those orgies of repeating, ballot-box stuffing, and election day riots with their torch-lit parades and bonfires, their bunting and barbecues—have vanished from the land.

“Elections nowadays are sissy affairs,” complained “Dock Walloper Dick” Butler even seventy years ago. “Nobody gets killed any more and the ambulances and patrol wagons stay in their garages. There’s cheating, of course, but it’s done in a polite, refined manner compared to the olden days. In those times murder and mayhem played a more important part in politics. To be a challenger at the polls you had to be a nifty boxer or an expert marksman. A candidate, especially if he ran against the machine, was lucky to escape with his life. I was lucky—I only had my skull bashed and my front teeth knocked out and my nose broken.”

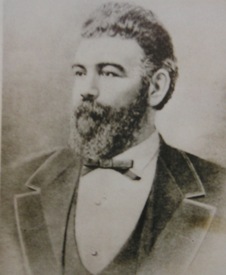

Few aspiring statesmen of our time have enjoyed a resume like that of the Hon. John Morrissey, who once told the United States House of Representatives: “I have reached the height of my ambition. I have been a wharf rat, chicken thief, prize fighter, gambler, and Member of Congress.” At times he seemed hard-pressed to separate his various metiers. Once, when irritated during debate, he roared, “If any gentleman on the other side wants his constitution amended just let him step into the rotunda with me.” It was not an empty threat.

Yet Morrissey was enormously popular, simply because he was his own man. His early career hinged on the electoral customs of his day. Each party and faction printed its own ballots. Voters brought a ballot to the polls and dropped it in the box. This simplicity permitted elaborations, exploited by Morrissey and his contemporaries, that are now almost fully comprehended and forbidden by the Election Law. There were repeaters, who voted more than once, either through multiple registrations or under names not their own. Morrissey was a gifted campaigner. “As an organizer of repeaters,” said the great William M. “Boss” Tweed, “he had no superior.”

The Hon. Timothy D. “Big Tim” Sullivan once explained his specialty, the bearded repeater. “When they vote with their whiskers on, you take ’em to a barber and scrape off the chin fringe. Then you vote ’em again with side-lilacs and mustache. Then to the barber again, off comes the sides and you vote ’em a third time with just a mustache. If that ain’t enough, and the box can stand a few more ballots, clean off the mustache and vote ’em plain face.” This made every man “good for four votes.”

A repeater needed some savoir faire. Up in Albany, a scruffy fellow once gave his name to the poll clerks as William Croswell Doane. “You don’t look like Bishop Doane,” a clerk objected. “Fuck you, man,” the repeater replied. “Gimme the goddamn ballot.”

Another technique was the “cannon” ballot, so named because just a few could blow the opposition sky-high. A contemporary of Morrissey’s wrote, “Ballots were easy to get, and we took plenty. Each candidate could get all he wanted. Why, kids even played with them. I got huge stacks of the ballots and carried them home to Mary.”

“Mary, put your irons on the fire,” I told her. She put three or four irons on the coal stove, and when they were nice and hot, we went to work on the ballots. We folded the ballots in sets of ten…and then Mary pressed the bundles of ten until they were thin enough to slip through the slit in the ballot boxes.

I distributed these ballots to my…workers and they slipped in ten at a time while the organization’s men thought they were doing a smart thing by piling in two at a time…One of my repeaters went to the polls twenty times and dropped in ten ballots every time. It was wonderful to see how my men… [preserved] the sanctity of the ballot [to] stop the corruption of Tammany Hall.

A poll clerk vigorously shook the box before opening it for the count, separating the cannon’s individual sheets to prevent its detection.

The Irish-born Morrissey apparently spent his youth learning to fight in barrooms and riverboats. He made his metropolitan debut in the Arena, Captain Isaiah Rynders’s saloon at 28 Park Row, across from City Hall. The Captain was a kind of political consultant, specializing in ballot-box stuffing and general mayhem on a cash retainer basis. Morrissey, whom an Arena habitue had addressed with inadequate respect, asked if any prize fighters were present, took off his cap, and said, “I can lick any man in the place.” Some eight men silently turned from their drinks, grabbed chairs, bottles, and other handy utensils, and rushed him as one. Nonetheless, Morrissey held his own until Rynders hit him under the ear with a spittoon.”

But Rynders, who admired men of spirit, had him carefully nursed until he recovered. Morrissey then became an immigrant runner. He met immigrants at the dock, found them work and shelter, and, after obtaining their pledges to vote the Tammany ticket, helped them obtain American citizenship, a simpler process in those days, that involved merely satisfying a single judge of one’s loyalty to the United States. (The Hon. Fernando Wood, when he was Mayor of New York, once managed to naturalize some 3,500 men in a day by sending them to a judge with preprinted cards requesting his signature as a personal courtesy.)

Once, when armed competitors attempted to drive him from a ship with belaying pins, a commentator described Morrissey clearing the decks “single-handed, like a young Ajax.” Testimony during the Tweed Ring scandals indicated tht the hardworking Morrissey had been convicted of assault with intent to kill and for burglary in 1849, serving 60 days. He was indicted three times in one day in 1857 for three separate assaults with intent to kill. And he was convicted of breach of the peace in 1861 and sentenced to a $50 fine and three months’ hard labor.

Busy as he was, Morrissey continued his professional development as a bare-knuckle boxer under the old London Prize Ring rules, the Marquess of Queensberry having not yet reformed the sweet science. The old rules were brutal: a round ended only when a fighter fell, was knocked down, or was thrown; matches ended when a fighter could not stand up at the beginning of a round. In 1858, Morrissey fought John Heenan, the Benicia Boy, for the Championship of America at Long Point, Canada. They battled for 32 minutes, during which, after Heenan broke his hand on a ring stake, Morrissey beat him into the ground “as a hammer beats a nail.” The New York Times, which found the spectacle a “triumph of brutality,” nonetheless, provided a blow-by-blow account.

Morrissey’s most renowned exploit was recounted by William E. Harding, longtime sporting editor of the late lamented National Police Gazette, in his 1881 biography, John Morrissey: His Life, Battles, and Wrangles, from His Birth in Ireland until He Died a State Senator.

Morrissey, during his visits to New York, became infatuated with a noted Cyprian, Kate Ridgeley, who was a mistress of Tom McCann, a noted rough and tumble fighter…Kate coquettishly pretended to think highly of Morrissey. This inflamed McCann’s jealousy, and when he met his rival in Sandy Lawrence’s house proposed to fight him for an undivided share in Kate’s affections…At the commencement of the fight McCann was successful, and threw Morrissey heavily. As he fell a stove was overturned, a bushel of hot coals rolled out, and Morrissey was forced on them. McCann held him there until the smell of burning flesh filled the room. The bystanders made water on the coals, and the gas and steam arose in McCann’s face and choked and exhausted him. Morrissey then…pounded McCann into insensibility. From that time until the day of his death Morrissey was called “Old Smoke.”

Such a man rose steadily in the world of mid-Victorian New York. He made a substantial fortune and married a beautiful woman. Retiring from the ring in 1859, Morrissey built a clubhouse and bought the racetrack at Saratoga Springs, N.Y., then a genteel watering hole. In 1866, he opened what were reputed to be the world’s most lavish gaming rooms on 24th Street in Manhattan. Some neighbors maintained that his casino lowered the moral tone of the community. Their wives, when the Morrisseys attended grand opera at the Academy of Music, glared at Mrs. Morrissey through mother-of-pearl opera glasses.

On a fuck-you basis, with the help of Tammany, Morrissey ran for Congress from the district in which his casino was located. He won handily and just to be sure nobody missed the point, ran a second time and was re-elected by an even wider margin. To celebrate his second victory, he commissioned a $75,000 pair of opera glasses in diamonds and sapphire from Lemaire of Paris as a gift for his beloved wife. They enabled the delighted Mrs. Morrissey to glare back at her detractors on opening nights.

After the Tweed Ring’s collapse during the early 1870s, Morrissey joined with Samuel Tilden and “Honest” John Kelly to control Tammany Hall. By 1875, he was serving as Police Commissioner, for which his experience with the criminal justice system eminently qualified him. But Tilden was then Governor of New York and running for President, leaving the Hall in the hands of Morrissey and Kelly. Their ambitions clashed. Kelly purged Morrissey, who then, having nothing better to do, won election to the State Senate from Tweed’s old district. Honest John’s followers said that only the district which had elected Tweed would send a vicious thug, a rowdy prize fighter, and a notorious gambler to the State Senate. These criticisms annoyed Morrissey because they hurt his wife’s feelings.

Accordingly, in 1877 he ran for the State Senate from the Seventh District, the most reputable in the City. Tammany orators denounced Morrissey as a gambler, prize fighter, ballot-box stuffer, and burglar. It was also said that when he had been in Congress, he had a percentage in Washington’s leading illegal faro game. All was for naught: Morrissey won by a huge majority.

He had defeated the respectables and the machine politicians alike. But Morrissey did not long enjoy his triumph. He had contracted pneumonia during his last campaign and, failing to shake it off, died at Saratoga on May 1, 1878, at the age of forty-seven. Over 15,000 mourners, including the Lieutenant Governor and the Attorney General, saw the dead statesman to his grave in St. Peter’s Cemetery, Troy, New York, where he lies with his family.