“Ah, Frank,” he said softly. “You’ve done grand things. Grand, grand things.”

“Among others,” Skeffington said.

Edwin O’Connor, The Last Hurrah

Eleven percent of all eligible New Yorkers voted on Tuesday, November 2, 1999. I was among them. I was also among a smaller minority. I was a candidate myself—for Richmond County district attorney on the Right to Life ticket. How did an Irish Catholic regular Democrat come to this?

I was a professional politician for the first nineteen years of my working life. I wrote speeches, newsletters, press releases, and brochures for several city officials, most of whom I remember fondly.

On my first day in the Manhattan borough president’s press office, I used the men’s room. Like the rest of the Municipal Building back in 1982, it was something of a museum piece, with massive five-foot-tall marble urinals that Toulouse-Lautrec could have comfortably used as a shower stall. (It is there, legend says, that the great editor Gene Fowler once asked of the cliché-ridden politician standing beside him, “Do you view with alarm or point with pride?”) A colleague passed me, stepped up to the plate, and gazed down. “I feel so inadequate,” he sighed.

The director of communications was a florid ex-tabloid reporter. He still looked like one of your classic Irish muckers, with a beer in his hand and a “fuck” on his lips. But his drinking days were over. They had been the stuff of legend. He had won a well-deserved award for reporting. Colleagues had helped him celebrate with enthusiasm, and he had come to consciousness in a Philadelphia house of carnal recreation—alone, I might add, and still in his clothes. He had $20 and a return ticket in his wallet, no recollection of the previous two days, and the kind of hangover that makes death an attractive option.

He had staggered from the Congressional Limited to the IRT #1. Emerging at West 72nd Street and heading for home, wishing West End Avenue a few blocks farther away, he’d passed the local laundry (ah! Anything to put off the inevitable) and picked up his shirts. He arrived home, finally, to find his wife fixing dinner. When she put down the knife and looked at him, he hefted the shirts and replied to her unspoken question, “He runs a great laundry, but the lines are so long.”

He was old-school, and his invective tended to be old-school. I never thought twice about it. But I recall once when he was ranting about a political opponent whom he kept referring to as “a cocksucker,” being surprised when another colleague—a quiet, reserved gay man—objected.

“I am a cocksucker,” he said, “and I really find this offensive.”

New York City politics seems sordid, petty and corrupt. Well, it is. That doesn’t mean it can’t be fun. As Donald T. Regan has said, “Power corrupts. Absolute power is a real gas.”

Occasionally, this truth spills into a public forum like the City Council. (“The difference between the City Council and a rubber stamp,” former councilman Henry Stern famously quipped, “is that the rubber stamp occasionally leaves an impression.”) Once, when the late Ted Weiss closed a speech to the Council by urging colleagues to “do the right thing,” the Honorable Dominick Corso of Brooklyn weighed in. “You think that takes guts?” he jeered. “It doesn’t take guts to do the right thing. What takes guts is to stand up for what you know is wrong, day after day, year after year. That takes guts!”

Most politicians are gray men: gray in their clothes and temperament, blending into the background. It’s protective coloring. I worked for only one colorful politician, an imposing, avuncular municipal statesman. Once, the statesman and I were going to City Hall. This was in early 1986. The gay rights bill was before the City Council. My statesman polled his district, found his constituents opposed and came out against it. The local gay-bashers, enraged by oncoming defeat, lobbied him anyway.

We had reached the escalator to the Woodside stop on the 7 line when a local scholar, a woman, slipped between the statesman and me to rant about the bill. My boss, probably irritated at my failure to body-block her, played the jolly fat man, chuckling benignly as we rode up the escalator. A train pulled in. People crowded the down side of the escalator. We were within five feet of the top.

At this point his face flushed. He roared, “No, lady! I won’t buy cocaine from you!” and rushed for the train. I followed. She remained, stunned on the platform. It’s been 13 years. She may still be there.

The statesman was opposed for Democratic district leader by an affable right-wing candidate who had unsuccessfully sought office some ten times. The rightist and his wife had seventeen children. He and I were passing out literature at a corner as an older woman came up. She took my stuff. She took his. She noticed the photograph of the candidate, his wife, and their brood. She flung the flier into his face, snarling, “You pervert!”

This job lasted about a year, until the statesman’s driver and I had a disagreement. The driver belted me in the face after I called him an asshole. (He was: he couldn’t resist graphic conversations with his girlfriend, then a discouraged use of the airwaves, and the statesman’s car phone had been disconnected as a result.) In a fatal moment, I told the boss that the driver went or I went.

I went. Good drivers are hard to find.

I enjoyed many such adventures until that life ended on December 31, 1993, when my then-employer, the last City Council president, left office and his successor chose not to retain my services. He and I had tangled before: I had expected it.

I am intolerant of political appointees who whine when a newly elected official fires them in favor of his friends. Having lived by the sword, I expected to die by it, and I did. Sic transit.

To a regular politician, silence is the paycheck’s price. If one’s opinions are not shared by one’s employer, remain silent or resign. But as a ronin, a masterless samurai, I now had no loyalties commanding discretion.

My opinions are largely conventional: I prefer solving immediate problems to enunciating long-range policy, most of which is bullshit anyway, and there is a lot of truth in the cliche that there is neither a Democratic nor Republican way of picking up garbage.

A few of my opinions, though, are outside the norm. For instance, I believe that despite the ranting about welfare, far more local government spending is largely the investment of public capital for private benefit, i.e., publicly funded improvements to privately managed facilities for immediate private profit and ill-defined public benefit, such as stadium projects for the West Side, Brooklyn, and Staten Island. This merely redistributes wealth from the working classes to the rich.

Issues represent not problems to be solved, but bloody shirts to inflame the rabble. V.O. Key Jr., in his classic Southern Politics in State and Nation, wrote of the Mississippi demagogue James Kemble Vardaman—aka “The Great White Chief”—that “His contribution to statesmanship was advocacy of repeal of the Fifteenth Amendment, an utterly hopeless proposal and for that reason an ideal campaign issue. It would last forever.” In the same vein, adequately funding Social Security, passing a state budget on time, or resolving rent regulation are never resolved. The politicians would then have to invent new issues.

Too many political activists use their activity as therapy: a licensed release for frustrated ambition, hatred, and need to control others. Politicians manipulate these fools to get elected, and later patronize them with little plaques for civic work, unpaid appointments to meaningless boards, or even unimportant paying jobs. Meanwhile, the pols enjoy the perks of office while shaking down businessmen for campaign contributions so their own good times won’t end.

Expressing in mixed company my belief that unborn children are human beings entitled to the right to life quickly placed me in outer darkness. So be it. One step led to another. The laws permitting abortion on demand, being wrong, should be changed by constitutional means. These include peaceful agitation, which includes running for office.

So I became a candidate.

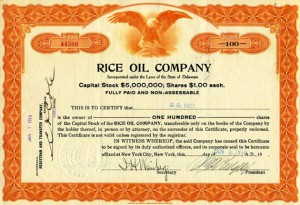

I had advised the Right to Life Party’s state chairman in February that I was available if the party wanted a candidate. One week before the July deadline for filing designating petitions, the local organization got back to me. The Staten Island Right to Life Party organization really isn’t. Organized. Seven or eight volunteers gather sufficient signatures on the party’s designating petitions to qualify its candidates for the ballot.

For the first day of filing, I was the only candidate in the book. Visions of lucky clerical errors danced through my wee little head. Then the others filed before the deadline. Damn.

The campaign was relatively quiet. William Murphy, the pleasant four-term incumbent Richmond County district attorney, had been nominated by the Democratic, Independence, Conservative and Working Families parties. If you went by his political support, he was running farther to the left and to the right than anyone since Norman Mailer ran for mayor on the slogan, “End fluoridation, free Huey Newton.” Catherine DiDomenico, the Republican challenger, though bright, spunky and articulate, was knifed before the campaign began by someone in the GOP apparatus who leaked that four or five other persons had turned down the nomination. And then there was me, Bryk, the lawyer.

The Association of the Bar of the City of New York, a starchy, self-congratulatory professional organization, interviewed the candidates through a committee of self-important men and women. I chose not to participate. I found the questionnaire intrusive.

My lack of faith in the integrity of the enterprise was rewarded when a committee member leaked its confidential deliberations to Murphy’s campaign, who leaked it to the local media. The association approved Murphy’s reelection, and did not approve his Republican opponent. Somehow “Not Approved” became “Not Qualified” in Murphy’s newspaper ads. DiDomenico’s friends counterattacked with a full-page newspaper ad accusing Murphy of favoring the Atlanta Braves over the New York Yankees, which seemed a little desperate to me.

My friends, I found, remained my friends regardless of their opinions on abortion. And audiences were generally polite. In my case, this is probably because (a) I’m polite, (b) I’m articulate and (c) everyone knew that I was going to have my clock cleaned on Election Day.

With the other candidates, I spoke at community forums, from the Staten Island Coalition of Women’s Organizations to the New Brighton Citizens Committee. Murphy calmly recited his accomplishments in office. DiDomenico attacked him as a weak prosecutor and advertised her experience as a legislative counsel and crime victims’ activist. I briefly talked about my background and argued for competent administration and the prosecution of environmental crimes; I occasionally answered questions about the death penalty (I’m against it) and the narcotics laws (I favor relegalizing drugs).

On Election Day, Murphy polled 62 percent, DiDomenico 37 percent and Bryk 2 percent.

Say not that the struggle naught availeth. I had fun, and besides, every man in politics deserves his last hurrah.

Hurrah.

New York Press, December 21, 1999