From New York Press, March 24, 1998

From New York Press, March 24, 1998

St. George, a city set upon a hill, the seat of Richmond County, is my hometown. On clear days, I look from my table across the Upper Bay to the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge, the Lower Bay, the sea, and the horizon, where the distant Atlantic Highlands sink into mellow blueness.

Merchantmen lie for hours or days at anchor, waiting for space in the Port of Newark or lightering cargo to a barge or coastal tanker. Other vessels pass, day and night: pleasure yachts, container ships, tug boats, auto transports, cruise liners, guided missile frigates. Fogs change this utterly. Here, the sea vanishes, then the bridge, the bay, the mansard-roofed 1881 brick mansion next door. Out of the swirling mist come the foghorns’ moans, punctuated by the deeper calls of the ships, feeling their way through the channels.

Despite radar and radio, the mists are still dangerous: in 1981, the Staten Island ferry American Legion was rammed amidships by a Norwegian merchantman during a heavy fog, seriously injuring several passengers and putting her out of service for months, her side smashed in the shape of the freighter’s bow.

Yet foggy or clear, twenty-four hours a day the ferries toot their diesel horns once as they depart the ferry slips at St. George on their five-mile voyage for Whitehall. The old names remain. Ferrymen are traditionalists. Sailing ferries were traveling the Upper Bay before the War of 1812, long before the five-borough City of New York was even a dream. Hence Whitehall and St. George, rather than Manhattan and Staten Island.

From St. George, the ferries bustle past the little pepperpot lighthouse on Robbins Reef. In the last century, when its keeper died in the line of duty, his widow was given the job in lieu of a pension. It was round-the-clock work. She lived in the lighthouse with her children. Every morning and afternoon, in all weathers, she rowed them to and from St. George, where they attended the public schools. They are all long gone; the lighthouse is automated.

From St. George, the ferries bustle past the little pepperpot lighthouse on Robbins Reef. In the last century, when its keeper died in the line of duty, his widow was given the job in lieu of a pension. It was round-the-clock work. She lived in the lighthouse with her children. Every morning and afternoon, in all weathers, she rowed them to and from St. George, where they attended the public schools. They are all long gone; the lighthouse is automated.

No trip is the same. Early morning skies can be delicate pink and silver, with the waves like mother of pearl. Or the horizon can be a thin line of fire, with a band of light sky beneath and rolling thunderheads above. The sunsets are often riotous with colors—outrageous scarlets, magentas, and purples, born of the pollutants emitted from the refineries along New Jersey’s Chemical Coast.

An incoherent would-be evangelist sometimes wanders the boat, his unmemorable ranting punctuated by “Praise God!” Cameras always click at the Statue of Liberty or Ellis Island as the boat begins rounding Governor’s Island to head into the Whitehall slips. Some evenings, the ferry is full of raucous, obnoxious drunks. The Manhattan skyline often seems a beatific vision, and I can only imagine my peasant grandfather’s emotions when he first saw New York from the deck of an immigrant ship in 1905.

If you have a choice, take one of the old car-carrying ferries, the John F. Kennedy, the American Legion, or The Gov. Herbert H. Lehman. Like their steam-powered predecessors, their second decks have outdoor seating at the bow and stern, and the third decks have a roofed promenade. Both classes of newer passenger-only ferries—the enormous Samuel I. Newhouse and Andrew J. Barbieri, and the tiny Alice Austen and John A. Noble—lack outdoor seating. You might as well be on the subway.

If you have a choice, take one of the old car-carrying ferries, the John F. Kennedy, the American Legion, or The Gov. Herbert H. Lehman. Like their steam-powered predecessors, their second decks have outdoor seating at the bow and stern, and the third decks have a roofed promenade. Both classes of newer passenger-only ferries—the enormous Samuel I. Newhouse and Andrew J. Barbieri, and the tiny Alice Austen and John A. Noble—lack outdoor seating. You might as well be on the subway.

Another ferryboat, the tiny Michael J. Cosgrove, sometimes moors at St. George for maintenance and repairs. She handles a .37 mile run up in The Bronx, from City Island to Hart Island. Although she is only sixty feet long, her passengers never complain of overcrowding. Most make only one trip, for her terminus is Potter’s Field.

Although the last steam ferries were built only fifteen years before the Kennedy class diesel boats, their melodious whistles sound no longer. The Cornelius G. Kolff and Private Joseph F. Merrill became prison hulks at Riker’s Island in 1987. After the Verrazzano was decommissioned in 1981, the City docked her at Pier 7, Staten Island. For the next two decades, people endlessly discussed converting her to a waterfront restaurant as a Connecticut businessman did the 1938 steam ferry Miss New York. Using her for something was better than letting her rot in the mud, like the old ferries Dongan Hills and Astoria, now at their last moorings among a hundred hulks off Rossville in the Arthur Kill.

Then Pier 7 collapsed into the harbor. Years of neglect can do that to a dock. (Perversely, cleaning up the river helped, too, since marine borers, for which a neglected pier is bread and butter, can now live in the harbor’s oxygenated water.) So a tugboat took the Verrazzano to Brooklyn. At least the City’s planning and execution seem consistent: when the tugboat’s captain arrived at Erie Basin with a 269-foot ferryboat, no one had told the Basin’s management that he was coming.

How did St. George get its name? It has little to do with the warrior-hero and martyr, always shown astride his rearing white horse, his lance impaling a dragon. Until 1886, the ferries landed at Clifton, further down the East Shore, the northern terminus of the Staten Island Railroad, an isolated short line controlled by the Vanderbilts (when it wasn’t in receivership). The future St. George was called Ducksberry Point, was undeveloped and even unpleasant waterfront real estate owned by one George Law, an entrepreneur regarded as something of a minor scoundrel but with a sense of humor.

There was also a man with a vision named Erastus Wiman, a bit of a hustler himself. (His first name is a Latinized version of the Greek erastos, meaning “beloved.” It was not a condition he would know throughout his life.) Born in 1834, Wiman came to Staten Island as an agent for R. G. Dun & Company of Toronto, which later evolved into Dun & Bradstreet. His manor house overlooking the Upper Bay was one of the finer residences on the island. If he had moved to Louisiana, he would have gone into oil. Having come to Staten Island, he went into real estate.

To enhance his investment’s value, he improved local transportation. In 1884, with the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad’s financial support, Wiman merged the ferries with the railroad to form one company, the Staten Island Rapid Transit. He wanted a new terminal for the Manhattan-bound ferries at the northernmost point on the island, where he had an option to buy George Law’s land.

The option was expiring and Wiman was short of cash to complete the deal. According to local historian William T. Davis, Wiman asked Law for an extension of time, promising only to name the new ferry terminal “in Law’s honor, but…with a title Law could hardly expect to earn either on his own or in his lifetime. Law thought it was all a fine idea [and] gave Wiman what he wanted.”

The B&O had an agenda: its own terminal facilities on New York Harbor. Wiman sold Robert Garrett, the B&O’s president, on building it at St. George. Wiman begged and borrowed every dollar he could and bought acre upon acre of Staten Island waterfront property, all of it mortgaged to the hilt as well. The B&O’s money financed the extension of the Staten Island Rapid Transit–from St. George along the island’s north shore over a huge railroad bridge to New Jersey. Once the connection was in place, Garrett and Wiman envisioned having the B&O’s passenger trains terminate at St. George, where passengers would take the ferries to Manhattan. They saw an enormous freight terminal, with barges carrying B&O freight cars throughout the harbor, and perhaps even a transatlantic shipping terminal, so passengers might pass from trains to liners. St. George would have become a great seaport. Erastus Wiman would have become filthy rich.

It never quite worked out. Garrett’s health failed and he lost control of the B&O, which went into receivership in 1891. The St. George project resulted in a big ferry terminal and freight yards, but no more. The B&O’s passenger trains never came to St. George. Two years later, R. G. Dun & Company accused Wiman of forgery. He was convicted in 1894, although the verdict was reversed on appeal. His empire of real estate, ferries, and railroads flew apart like autumn leaves in a high wind.

Ten years later, Wiman died. He kept his fine house to the end. But a week before his death every stick of furniture he had–save his actual deathbed–was auctioned off for the benefit of his creditors. After his conviction, even the Staten Island Rapid Transit changed the name of its ferryboat from Erastus Wiman to Castleton, after one of Staten Island’s towns.

The Staten Island Rapid Transit gradually dwindled to a passenger commuter line, losing its last freight customers in 1979. The great Arthur Kill railroad bridge, still the largest vertical lift span in the world, was embargoed from 1991 to 2007, when freight service was restored along part of the North Shore line, still Staten Island’s only link to America’s railroads.

Even the one mayor who had great dreams for Staten Island saw them fail. John F. “Red Mike” Hylan, Mayor from 1918 to 1925, was an old-fashioned Democrat from Brooklyn with a full head of red hair and an enormous mustache. With Thomas Jefferson, he would have “strangled in their cradles the moneyed corporations, lest their organized power oppress the people.” M.R. Werner, a New York World reporter, said wrote that he was “…possessed of…the loudest voice east of Omaha.”

When he spoke from the steps of City Hall, small children burst into tears at 23rd Street, and the echoes of his eloquence drowned out the low moaning of the tugboats as they skittered down the bay. His tonal quality is hard to describe; it was somewhere between the trumpeting of an enraged elephant and the rumble of underground blasting, and the miracle was that his passionate outcries did not split his throat from ear to ear.

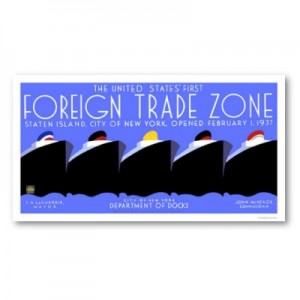

Hylan apparently enjoyed fighting more than winning. His was the kind of open mind that sometimes, as Damon Runyon observed in another context, “should have been closed for repairs.” He dreamed of building a free port in Stapleton, a ten-minute walk from St. George, and spent millions of tax dollars on piers, warehouses, and rail connections.

Unfortunately, first the Congress of the United States declined to cut tariffs or pass special legislation to exempt the Stapleton free port from them. Then, container ships replaced the old freighters. There was no incentive to rebuild the Stapleton facilities. The warehouses fell into ruin, the piers collapsed into weathered stumps, and the railroad tracks were paved over.

Hylan envisioned a railroad tunnel under the Narrows from Staten Island to Brooklyn, linking the SIRT with the subway of the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Company in Bay Ridge. His eloquence was so persuasive that the B&O lent $5 million to the SIRT for complete third-rail electrification comparable to that of the BMT. The City even began digging the tunnel.

Then Hylan was defeated by James J. Walker at the 1925 Democratic primary. After Walker took the oath, he canceled the project. (Some years later, asked why he had appointed Hylan a Judge of the Children’s Court, Walker replied, “So the kids could be judged by their peer.”) Hylan Boulevard, which bears his name, runs from Victorian photographer Alice Austen’s gingerbread cottage on Upper New York Bay at Clifton across the South Shore to Tottenville, on the Arthur Kill, across from Perth Amboy.

Even the Homeport, the naval base built a decade ago in the hope that some defense dollars might drop into the local economy, was scheduled for closing before it was finished. Most of the money and jobs went to out of state contractors. Stapleton’s streets are still lined with shuttered bars and night clubs.

Thus, Staten Island is the isle of forgotten dreams and St. George, the fruit of a real estate deal, its sleepy capital. St. George’s relative poverty has encouraged development elsewhere, so it has become a backwater with convenient transportation. Its ethnic and religious diversity are astonishing; its quiet streets are lined with buildings from the bombastic to the boarded-up: courthouses like classical temples; a Babylonian movie theater; a Carnegie library; a 1920s Georgian bank, and numerous Victorian gingerbread mansions, ranging from exquisite restorations to rundown boarding houses.

Above all, almost literally, is Borough Hall, a Beaux Arts French chateau with an Italian Renaissance tower (its narrow windows presumably ready for the Borough President’s use in pouring molten lead on his enemies), its illuminated clock guiding the ferries home, its bells gently striking every hour. Architecturally incoherent yet romantic, imposing, and homey, Borough Hall has dominated St. George without oppressing it for nearly a century.

Erastus Wiman no longer schemes in his manor house. The SIRT’s old camelback steam locomotives no longer wheeze about the St. George railroad yards. But the ferries still run, quiet largely reigns, and beyond my window the wooded hills roll down to the sea.