The first month’s name honors the god Janus, whose two faces let him simultaneously contemplate past and future. I suspect most of us look backwards, contemplating time spent, which increasingly for me is marked by death.

In my college’s quarterly alumni newsletter, nearly 25 years after my graduation, an increasing number of familiar names appear among the obituaries. I was throwing out old papers in yet another failed attempt to clean my office when I noticed an obituary I had clipped from The New York Times. Michael Rosano, who was and still is my friend, died a little more than a year ago, on October 13, 2000. He was 42 years old. He was a rarity: a political animal who was also a human being.

I first met him 20 years ago this month. On January 1, 1982, I attended the inauguration of Andrew Stein as Manhattan borough president. I would work for Stein, on and off, for the next 11 years. (My rabbi, Walter McCaffrey, introduced me to the Stein staff. Walter is neither Jewish nor a religious sage, although one would always be better off for heeding his wise advice. According to Lardner and Reppetto’s NYPD, this use of the word “rabbi” is peculiar to New York, dating from the late 19th century when some Irish Catholic police officer first used the term to refer to the senior officer or politician, usually also Irish Catholic, who was his mentor, protector, and counselor.)

Anyway, I was by then a self-taught editor and speechwriter, so I ended up in the Borough President’s press office, where Michael’s desk was conveniently located in the far corner, out of the line of sight of anyone bursting in the door to see the press secretary. Michael and I both came from Albany County: he from the city of Albany and I from Latham, which is, as F. Lee Bailey once said in a courtroom speech, “an unincorporated hamlet.” Albany is the last fortress of upstate yellow-dog Democracy. Among the family legends is my grandfather’s explanation of an infected hand: he had brushed the GOP lever on a voting machine. Even Michael only once admitted to voting for a Republican, although he was excused his apostasy because she was a woman and an Italian, and she lost.

Michael was darkly handsome, gentle, and dryly humorous. He often claimed that, although born of Italian heritage and a gay man (someone once called him “the capo di tutti frutti”), his soul was that of an uppity Jewish woman from the Upper West Side. A few weeks ago, while watching Robin Bartlett’s wonderful performance in Richard Greenberg’s Everett Beekin, I found tears in my eyes because, somehow, her manner and intonation vividly reminded me of my friend’s manner of camping it up.

We both took politics seriously while taking politicians lightly, so we hit it off. He had studied English literature at New York University and written for the school’s daily paper. Occasionally, after the second or third drink, he murmured about interviewing Sid Vicious at the Chelsea Hotel. “Mr. Vicious,” as Michael insisted on calling him, had received Michael in the squalid room the singer then shared with Nancy Spungeon. Sid was nearly stupefied when he opened the door to the boy reporter, and his answers were increasingly tangential and then incoherent. Finally he fell asleep between one sentence and another. Michael called the musician’s name a couple of times. The only replies were snores. Michael picked up his notebook and stole silently away.

Michael entered politics in 1976, when he volunteered to work for the great Bella Abzug in her Democratic primary campaign for the U.S. Senate against Daniel Patrick Moynihan. Michael was unusual for an 18-year-old in politics: he was efficient, hardworking, and enduringly patient, and Mrs. Abzug’s managers took note of him. After his graduation from NYU, Michael briefly worked at Channel 13, where, as in most not-for-profit organizations, the infighting might have tested the political skills of the Borgias. Then he came to the Manhattan Borough President’s office.

Michael was the first openly gay man whom I knew well. He told me that he had known from childhood that he was gay (I found nothing odd in this: I knew I liked women at the age of six, although I could not have told you why). His family loved him; his colleagues trusted and respected him. Nonetheless, he felt alienated, with a mild sense of always being the Other nearly everywhere save among his friends or among gay people. Despite his gracious manners and self-control, he bitterly resented anyone who did not accept his right to live as he wished without criticism or discrimination. In particular, he developed an antipathy to organized Christianity in general and Roman Catholicism in particular, although his relationships with individual priests and ministers were often quite friendly.

We have lived with AIDS as both a disease and a political question for nearly a generation. It first became prominent during the initial year or two of our friendship. Back when a citizen could still stand on the front steps of City Hall without the mayor’s prior permission, ACT UP, the gay and lesbian activist group, chained shut the Hall’s doors as protest against some forgotten municipal failure. I was then inside the building, sitting at a desk. In common with most folks in City Hall back in those days, I felt inconvenienced but not terrorized. Politicians then understood that being the target of the public’s wrath was part of the job description. Probably we understood too that, at best, most City Hall politicos are hacks with good intentions. We would have laughed to think ourselves as important as city politicians seem to think themselves now—so essential to public life that they must be protected by effectively barring the people from City Hall.

Anyway, there was not much else to do until the guys from the Department of General Services appeared with the bolt cutters. The telephone rang. It was Michael. From my point of view, he was safely across the street in the Municipal Bldg.

“What’s happening?”

“Well,” I replied, “we’re being held hostage in City Hall by gay terrorists.”

“In your case, they have a good reason,” he replied, and hung up.

His experience of seeing friends die radicalized and hardened him. He believed that the government was responsible for solving the problem, in part because the public sector can throw an infinity of tax dollars at a problem, which many believe will solve it sooner or later; in part because he did not believe the free market would devise an affordable cure for the disease in time to save his friends; and in part because his political ideas were expressed through the rhetoric and legal precedents of earlier civil rights movements, all of which had relied on state intervention to further their agendas. He thus focused his talents on furthering government intervention by learning how one quietly amended statutes or modified budgets, the kind of practical political work that few ideologues bother to master because it often requires years of heartbreaking work.

As Michael gradually became an insider, he never forgot being an outsider. This meant his more radical acquaintances hurt him more deeply than they could have known when they called him a sellout. The best proof of Michael’s humanity was that he could tell these idiots to go to hell, and mean it, and still take their calls the following day.

He never lost his humanity. A Democrat clubhouse lawyer told this Michael Rosano story over drinks at Dusk on 24th Street. This guy intends to marry his girlfriend at a big formal event on Cape Cod in June 1991. He decides to go through a civil ceremony in front of a judge in November 1990 so the girlfriend might share his health insurance benefits. They get the license from the city clerk. Then the lovebirds realize they need two witnesses to the ceremony. For that matter, they need a celebrant. On the morning of the blessed event, this guy pokes his head into the office of the judge for whom he then works and asks whether she would mind performing the ceremony that afternoon. The judge, whose infinite patience is much taxed by this guy, replies, “Yes, I’ll do it. You really believe in advance notice, don’t you?”

The would-be bride talks her cousin, the pastry chef, into being her witness. The guy has a busy day and understandably forgets about getting his witness until about an hour before the big event. At the 11th hour, he knows there is only one man he can rely on. Like several thousand people who have outrageously imposed on Michael in the past, this guy is right.

He sprints from the Tombs to the Municipal Building, takes the elevator up to the 15th floor (there were no metal detectors in the lobby then) and sticks his head into Rosano’s office. Rosano, as usual, is on the telephone. This guy asks Michael to stand witness at his wedding in 15 minutes. “Sure,” Rosano replies. “Thanks for all the notice.”

The judge is conducting a murder trial when Michael, the pastry chef, and the blushing bride, in Dior suit and big hat with bouquet in hand, sweep up to the courtroom door. A court officer asked, “Who’s getting married?” The bride, who then and throughout her marriage is never at a loss for words, seizes Rosano’s hand and replies, “Michael and I are tying the knot.” Michael and the court officer arch their eyebrows into their respective hairlines. As the bridal party enters the courtroom where the judge is conducting a murder trial, the Assistant District Attorney asks the witness, “Is this the knife that you saw in the hand of the defendant?” Michael turns to the bride and pats her on the arm, murmuring, “So auspicious for our wedding, dear.”

He moved from government to lobbying and back to government, ending his career as deputy communications director to state Sen. Martin Connor, then the minority leader of the state senate. He worked harder than ever, and as do most who remain young in spirit, neglected his health, certain that he would live forever. When he was finally diagnosed with cancer, his condition was nearly untreatable.

Michael was as principled in death as in life: his estrangement from the church in which he had been born and raised was so profound that he requested no religious service over his remains. Last spring, his friends celebrated his life at New York University. Every seat was taken and there was standing room only in the hall. There was some rhetoric, which he would have tolerated, having written a bit of it himself. However, those who knew him best spoke of his hard work, kindness, wit, and blithe courage in the face of his own death, which takes some doing. One speaker called Michael a foul-weather friend, and quoted Maurice Baring’s “In Memoriam, AH,” which seemed right:

No one shall take your place.

No other face

Can fill that empty frame.

— January 8, 2002, New York Press

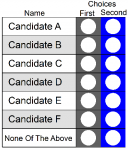

The option of voting for “None of these Candidates” or “None of the Above”—NOTA for short—enjoys support on both left and right. The Wall Street Journal endorsed NOTA in 1996, after Representative Wes Cooley of Oregon was re-nominated despite being exposed as both a fraud and a phony war hero. Although unopposed at the Republican primary, Cooley received only 23,000 votes while 31,000 voters cast blank ballots or various write-ins. The voters had no effective way to deny his re-nomination. This was two years after Representative Mel Reynolds of Illinois was re-elected unopposed following his post-primary indictment for raping a minor, possession of child pornography, and obstruction of justice. (Later convicted, forced to resign, and imprisoned, Reynolds was pardoned by President Clinton on his last day in office

The option of voting for “None of these Candidates” or “None of the Above”—NOTA for short—enjoys support on both left and right. The Wall Street Journal endorsed NOTA in 1996, after Representative Wes Cooley of Oregon was re-nominated despite being exposed as both a fraud and a phony war hero. Although unopposed at the Republican primary, Cooley received only 23,000 votes while 31,000 voters cast blank ballots or various write-ins. The voters had no effective way to deny his re-nomination. This was two years after Representative Mel Reynolds of Illinois was re-elected unopposed following his post-primary indictment for raping a minor, possession of child pornography, and obstruction of justice. (Later convicted, forced to resign, and imprisoned, Reynolds was pardoned by President Clinton on his last day in office