From New York Press, January 20, 1999

Some years ago, the Postal Service issued a stamp commemorating Belva A. Lockwood, Esq., whom the agency believed had been the first woman Presidential candidate. In 1884 and 1888, Mrs. Lockwood waged symbolic campaigns (she appeared on no ballots and received no votes) to publicize the cause of women’s suffrage. The first woman admitted to the Illinois bar, Mrs. Lockwood was apparently a paragon of respectability, as worthy of postal honors as, say, Richard Nixon, the unindicted co-conspirator.

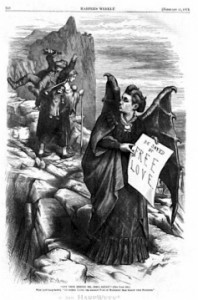

The Postal Service got the essential thing wrong. The first woman Presidential candidate was the eloquent, beautiful Victoria Claflin Woodhull—adventuress, editor, actress, revolutionary, Spiritualist, fortuneteller, blackmailer, seductress, and prostitute. Caricatured by Thomas Nast as “Mrs. Satan,” Vickie was many things, but never respectable.

Born in 1838, she claimed—like Salvador Dalí—to recall the moment of her conception. Her father, Reuben Claflin, was a remarkably vile con artist and snake-oil salesman without a redeeming quality, who robbed his neighbors, defrauded insurers, stole from his children, and pimped his daughters. According to Barbara Goldsmith, her most recent biographer, Vickie’s illiterate fortune teller mother was never quite sure of her first child’s father. Another daughter, Utica, became an alcoholic who hustled johns outside her sisters’ offices.

Yet Vickie had striking good looks, quick intelligence, and heaven-storming eloquence. Her sister and partner, Tennessee, was less complicated, more loving and sensible, and utterly loyal. Tennie’s other personal qualities generally proved useful in negotiating with individual men when Vickie’s eloquence was not persuasive: luxuriant auburn hair, pretty features, a great body. Tennie was a babe. They were a good team.

From childhood, Vickie had seen visions and sincerely believed herself under the protection of Demosthenes. By the time she was eleven, she could declaim with ecstatic fervor, and her father hauled her around Ohio to preach. After Tennie developed second sight, Dad had her conduct seances, too. Dad always took up the collection.

At fifteen, Vickie eloped with Dr. Canning Woodhull, an alcoholic weakling whom she soon divorced. In 1858, she began appearing on the San Francisco stage in melodramas such as The Country Cousin and New York by Gaslight, where, as Goldsmith writes, “low décolletage and tightly laced bodices emphasized breasts that were semi-exposed, elevated, and served up like ripe melons.” After the performance ended, the revels began, and Vickie gave good value for money.

Two years of this were enough. Vickie went home to take up magnetic healing. her charisma, honed through years of preaching, acting, and whoring, let her cure the sick and foretell the future. Meanwhile, Tennessee was handling up to ten gentlemen callers a night.

In 1868, Vickie and Tennie went to New York. The sisters knew where their talents lay, and wangled an introduction to Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. The dashing old pirate had risen from running a ferry boat to directing the New York Central Railroad. Tennie’s charms worked their magic. Although her medical training was limited to pitching her father’s snake oil, she became the Commodore’s “therapist,” administering enemas, manipulating his prostate, and, according to Goldsmith, providing “…magnetic healing”:

With her left hand acting as a negative magnet, the right as a positive, she claimed to reverse the polarity of his body and to expel negative energy.

Who could doubt it.

The sisters provided Vanderbilt with stock market advice, courtesy of the spirits. His correspondence shows he paid them a two percent commission on his business transactions based upon their forecasts. In 1869, with Vanderbilt’s support, the sisters formed a brokerage house, Claflin & Woodhull. The amused press called them “the Fascinating Financiers.”

Vickie published Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly from April 1870. In its pages, she announced her 1872 Presidential candidacy. Her platform was revolutionary, as one would expect from the president of the American section of Karl Marx’s International Workingmen’s Association. She too received no votes. (Marx detested Vickie, considered her social platform irrelevant to the class struggle, and eventually purged her.)

In December 1870, the matriarchs of the suffrage movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, had been scolded by a member of Congress for even asking that a women’s suffrage amendment be passed from the Judiciary Committee. That evening, they learned to their resentment that the Committee had granted one Victoria Woodhull a hearing to present a memorial on woman suffrage. Vickie’s success won her the undying enmity of the feminist establishment.

Unlike most suffragists, Vickie favored equal rights for everybody. Some were surprised in the summer of 1998 when Hillary Rodham Clinton praised Mrs. Stanton in a speech at Seneca Falls, New York. Mrs. Stanton resented the enfranchisement of African-American men. Indeed, she seemed incapable of speaking about them without using the word “Sambo.” Also, she emphasized granting the vote to educated women. Universal education was then largely unknown. Mrs. Stanton did not want votes for the cleaning woman and the maid. She wanted suffrage extended only to the educated lady elite, such as herself.

Vickie had pulled off her coup through her most able political ally. Benjamin F. Butler was a squat, wall-eyed, remarkably ugly Congressman. He was brilliant and audacious. Francis Russell notes that during his oral examination for admission to the Massachusetts bar, he disagreed with an opinion the examining judge had rendered earlier in the day. The judge reversed the opinion and made Butler a lawyer on the spot.

A perennial gubernatorial candidate, coarsened by a lifetime’s grabbing for the main chance, Butler was tough, crude, and vain, an opportunist and adventurer. Elected on his sixth try in 1882, Butler was denied the honorary doctorate Harvard traditionally awarded to the Governor of the Commonwealth. But he and Vickie struck it off well.

Yet Butler was radical as well as corrupt. The genius he usually directed at concealing evidence, eliciting perjury, and enacting special interest legislation was also employed in the cause of African-Americans and women. He was sincere when he said, “God made me only one way. I must always be with the underdog in the fight. I can’t help it; I can’t change it; and on the whole, I don’t want to.”

Confronted once with a rumor that he had offered to help Vickie in the cause of woman suffrage in exchange for a chance to “feast his eyes upon her naked person,” Butler replied, “Half truths kill.” Goldsmith notes that Vickie knew Butler well enough to remember his midnight snacks of doughnuts washed down with whiskey. But whether Vickie and Butler were lovers is as irrelevant as it is unclear. He proved a consistent, ruthless, and effective champion of human rights. Rarely has so blatant a cynic become so embattled a reformer.

On January 11, 1871, Woodhull addressed the committee. She argued Congress did not need to amend the Constitution; Article IV, Section 2 and the Fourteenth Amendment already provided the right to suffrage for all citizens. Congress only needed to pass a declaratory act to enable women to vote. Senator Charles Sumner later said no one could answer her legal arguments. In the end, the committee still defeated her proposal.

She had always championed free love. Vickie believed the institution of marriage was tyranny; married men and women who no longer loved one another should be free to take up other relationships; and unloving marriages essentially constituted a form of sanctioned prostitution.

The Reverend Henry Ward Beecher, pastor of Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights, preached a different sort of sexual emancipation. Driven by his need for adulation and crude physical lusts, Beecher blurred the identify between revealed Christianity and a vague adherence to the teaching and example of Christ in a self-indulgent, flabby theology he called the Gospel of Love.

Immensely popular among the elite, Beecher had a string of affairs with female parishioners and other women. On October 10, 1868, he seduced Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of Theodore Tilton, a journalist and one of his parishioners. Mrs. Tilton confessed to her husband. Tilton, who had been one of Beecher’s friends, threatened to expose Beecher.

Goldsmith confirms that there was a cover-up, largely because Plymouth Church had been financed by bonds depending on the collection plate for their repayment. Beecher was the box office draw. If he were driven from the pulpit, the men who had bought the bonds stood to lose their money. But the Beecher-Tilton affair, too, became an open secret. Many feminists who corresponded with Vickie wrote about it, often from personal knowledge of one or more of the participants.

Because Beecher had practiced free love without admitting it, Vickie outed him as an adulterer and lecher, right on the front page of Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly for November 12, 1872. She described what Beecher and Mrs. Tilton had done, reprinting letters from Mrs. Stanton and other feminists to support her claims. Beecher did not sue for defamation. But Anthony Comstock charged Vickie and Tennie with obscenity, namely, for using the phrase “red trophy of her virginity,” a quotation from the Book of Deuteronomy. The sisters would be repeatedly arrested and jailed for months.

Because Beecher had practiced free love without admitting it, Vickie outed him as an adulterer and lecher, right on the front page of Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly for November 12, 1872. She described what Beecher and Mrs. Tilton had done, reprinting letters from Mrs. Stanton and other feminists to support her claims. Beecher did not sue for defamation. But Anthony Comstock charged Vickie and Tennie with obscenity, namely, for using the phrase “red trophy of her virginity,” a quotation from the Book of Deuteronomy. The sisters would be repeatedly arrested and jailed for months.

According to Goldsmith, Comstock (the self-proclaimed “Roundsman for the Lord”) was an obsessive masturbator. His sexual guilt drove him to a lifelong pursuit of pornography, dirty playing cards, and the whole gamut of sexual devices, appliances, and toys. Amid the splendors of the Gilded Age, Comstock saw only dirty pictures. He was a little too enthusiastic about showing off his porn collection; a little too proud of the badge and gun a craven Congress permitted him to carry as a special postal agent.

Against so inexorable a force, what could Vickie do but to retain William F. Howe, the late nineteenth century’s sleazy lawyer par excellence. Howe usually represented murderers, thieves, fences, pimps, and whores. He could persuade juries that a defendant’s trigger finger had slipped not once, but six times. He found Anthony Comstock child’s play. On the day of his summation, Howe demanded to know if Deuteronomy and Fielding were obscene, asked why the court had not issued an order to seize the works of Smollet and Byron, and won over the jury with a fine, roaring speech: “O Liberty, where are thy defenders?…Must it be as the poet says: ‘Truth forever on the scaffold,/ Wrong forever on the throne?'”

In 1877, Vickie and Tennie went to London. After a friendly discussion about Cornelius Vanderbilt’s personal life with William Henry Vanderbilt, the late Commodore’s son, a small fortune had been placed at their disposal provided they left the country. Vickie married John Biddulph Martin, an English banker, and spent the rest of her life striving for a respectability she could not win.

But Tennie had a grand time. In 1884, she met a wealthy widower, Sir Francis Cook, told him the spirit of his dead wife had advised her to marry him, and did. Lady Cook (who, upon her husband’s ennoblement by the King of Portugal, also became known as the Vizcondesa da Montserrat) entertained lavishly throughout a loving, happy marriage. She remained beautiful, witty, charming, and open until her death in 1923.

Vickie joined her among the spirits in 1927. In a niche of her library, where she died, was a shrine to Nike. Being Vickie, she sometimes murmured that in another life she too had been the winged goddess of victory.