December 20, 1860 South Carolina seceded from the Union in response to Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency. “Poor South Carolina,” exclaimed James L. Petigru, one of the Palmetto state’s few Unionists. “Too small for a republic, too large for a lunatic asylum.”

On January 6, 1861, as other Southern states followed suit, Fernando Wood, mayor of the City of New York, issued an official message to the Common Council, a body sometimes called “The Forty Thieves.” Calling secession “a fixed and certain fact,” the Mayor proposed the City secede too, becoming an independent city-state. This, as Abraham Lincoln commented, was like the front doorstep setting up housekeeping on its own.

Wood was born in Philadelphia on June 14, 1812. His mother named her son after the swashbuckling hero of The Three Spaniards, a novel she read during her pregnancy. [In Tweed’s New York, Leo Hershkowitz cites a story that Wood was “reported to have entered New York as the leg of an artificial elephant in a travelling show,” [if this is still Hershk. then either quote it straight or find a way to recast it; this is too termpapery…]and became the manager of a “low groggery” on the waterfront, dealing in liquor and “segars.” In 1839, his business partner, Edward E. Marvine, sued him for fraud, but Wood successfully pled the statute of limitations, which Marvine had missed by a day.

Wood was slender, erect, about six feet tall, and strikingly good-looking, with dark blue eyes and coal black hair. (In later years, he dyed it.) He was dignified, eloquent, and self-possessed: he seems never to have lost his temper. At the age of twenty-eight, he was elected to Congress for one term. Defeated for reelection, Wood went back into business. M.R. Werner, in Tammany Hall, reports that his merchant barque, the John W. Cater, was the first supply ship into San Francisco after the discovery of gold on Sutter’s farm. When its cargo sold at an immense profit, Wood kept it all by cheating a new partner of his fair share. Wood then retired from business and became a statesman.

In 1850, he narrowly lost his first campaign for mayor. Four years later, he ran again. This time, Wood was supported by old toughs from Tammany Hall and young toughs like the Dead Rabbits. These last, a band of thugs who loved fighting for its own sake, had been part of an informal militia, the Roach Guards, named after a prominent liquor dealer. Someone had enlivened a meeting by throwing a dead rabbit into their midst. “Dead rabbit” was then slang for “really tough guy.” [was the term current before? or did the incident create the slant? not clear]The incident was an inspiration.

Today, a politician might reflect for some time before openly accepting support from the Crips or Bloods. [or you could point out that NY pols were following in a noble tradition; Roman elections couldnt’ ahve existed without similar gangs of thugs] Wood had no qualms. After all, the campaign proved violent, and their support was useful. Wood was sanguine: he claimed the people “will elect me Mayor though I should commit a murder in my family between this and the Election.” He was elected by 1,456 votes, receiving 400 more votes in the “Bloody Sixth” ward than there were voters. Some argued this was merely a clerical error.

When Wood was elected[if all his misdeeds had been of a private and eprsonal nature, how did they know he was a baddun? why were they vilifying him?], the Morning Courier and Enquirer wrote:

Well, it now appears that Mr. Wood is Mayor… Supported by none but ignorant foreigners and the most degraded class of Americans, Mr. Wood is Mayor. In spite of the most overwhelming proofs that he is a base defrauder, Mr. Wood is Mayor. Contrary to every precedent in the allotment of honor through a municipal history of nearly two hundred years, Mr. Wood is Mayor. His assertion to us that a murder by his own hands could not prevent his election had reason in it; Mr. Wood is Mayor.

Yet, during his first term of office, Wood proved efficient and hardworking, often personally leading the police in breaking up riots and closing down illegal bars. He maintained a complaint book at City Hall, and often personally investigated entries.

His second term was different. He won by 10,000 votes in 1856, and probably his entire margin of victory was fraudulent. Election Day riots broke out in the First, Sixth, and Seventeenth wards, with the Dead Rabbits battling the Bowery Boys, smashing ballot boxes and terrifying opposition voters. Wood apparently foresaw the advantages of chaos: he had furloughed the police for the day.

Wood now realized his opportunities and he took them. [Isn’t that “Plunkett?”] He sold appointment as corporation counsel, the city’s lawyer, to two different men at the same time, for cash. He sold the police commissionership for $50,000. He sold the street cleaning contract to a high bidder after arranging a $40,000 bribe to the Common Council and a twenty-five percent interest in the profits for his beloved brother Ben. Most memorably, Wood allowed City Hall to be sold at auction to satisfy a judgment against the City. [what does that mean?]

The Legislature in Albany now shortened Wood’s term to one year. They created a state-controlled Metropolitan Police Force and ordered the Municipal Police dissolved. Wood had none of it. Do you mean he “was having none of it?” On June 16, 1857 when the state tried taking over the Street Cleaning Department, Wood ordered the Municipal Police to physically remove the state appointees from their offices, and this was done. The state authorities obtained an order to arrest Wood for inciting a riot. Capt. George Walling, a redoubtable ex-Municipal turned Metropolitan, went into City Hall alone to arrest Wood. The Mayor greeted him cordially, learned of his mission, turned to his Municipals and said, “Men, put that man out.” Walling seized Wood, according to Luc Sante, and began dragging him toward the door. Then the Municipals laid hands upon Walling, freed the Mayor and tossed Walling down the front steps.

Some say they merely escorted him out, for old-time’s sake. [Don’t get it]

The Metropolitans now marched fifty strong from their White Street headquarters to find City Hall held in force by the Municipals. They charged up the front steps as the Municipals issued forth with a cheer to meet them, and the air was filled with the sound of locustwood clubs, which “emitted a sound like a bell”[???source???] on hitting human skulls. The Municipals outnumbered the Metropolitans, and drove them back. The state forces rallied, however, and charged City Hall once more. At this moment, the Dead Rabbits and “a miscellaneous assortment of suckers, soaplocks, Irishmen, and plug-uglies, officiating in a guerrilla capacity,” [???source???] rushed the Metropolitans from the rear.

“The scene was a terrible one,” wrote The New York Times. “Blows upon naked heads fell thick and fast, and men rolled helpless down the steps, to be leaped upon and beaten until life seemed extinct.”

The day was saved by the 7th Regiment, then marching down Broadway to embark for Boston. The Metropolitans requested help. The gallant 7th, drums rolling, flags flying, turned toward City Hall. The Mayor capitulated.

For several weeks the city was patrolled by two police forces working at cross purposes. A Municipal might arrest some thug only to have a Metropolitan set him free. Each side freely raided the other’s precinct houses to liberate prisoners en masse. The gangs found this stimulating: on July 4, 1857 the Dead Rabbits and Bowery Boys started a two-day battle in the area around Mott, Mulberry, Bayard and Elizabeth Streets, leaving eight dead and 100 wounded in a whirl of stones, brickbats, clubs, and gunfire. In the fall, the courts determined that the City’s ancient royal charters were meaningless and the City was no more than a creature of the State. The Municipals hung up their clubs and badges.

Tammany’s 1857 convention nominated Wood by a vote of 100 to five for his only opponent, William M. Tweed, who would be heard from again. Nonetheless, in the fall elections, Wood proved that not even Wood could survive financial panics, police riots, and the foreclosure sale of City Hall. Within a year, however, the Model Mayor defeated his successor for reelection and returned to power. In common with most Democrats, Wood opposed the abolition of slavery out of both personal racism and belief in the City’s dependence on the cotton trade. [the logic of this paragraph is giving me whiplash]

To be sure, he did not publicly dwell upon the lottery concession that his brother Ben and he held in Louisiana, which someone once described as akin to being given a color offset lithographic machine by the Federal Reserve with the injunction: “Now go ahead and print all the one hundred dollar bills you need.” [again, I don’t get this, or how what comes next follows from it] In a speech at New Rochelle in 1859, Wood argued that the city’s prosperity depended on Southern trade, “the wealth which is now annually accumulated by the people…of New York, out of the labor of slavery—the profit, the luxury, the comforts, the necessity, nay, even the very physical existence depending upon products only to be obtained by the continuance of slave labor and the prosperity of the slave master.”

This was not oratory. By 1860, according to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, the city’s largest industry was garment production, with 398 factories employing 26,857 workers to create clothing worth $22,420,769—largely from Southern cotton. Sugar-refining, the second largest, also depended on Southern cane to refine sugar products worth $19,312,500. These two industries created more than a quarter of the city’s gross industrial product.

Losing Southern raw materials might devastate the city’s economy. As Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace note in Gotham, “the city’s key economic actors—the shipowners who hauled cotton, the bankers who accepted slave property as collateral for loans, the brokers of southern railroad and state bonds, the wholesalers who sent goods south, the editors with large southern subscription bases, the dealers in tobacco, rice and cotton—all had come to profitable terms with its slave economy.” They feared that secession would mean massive Southern defaults: the nonpayment of bills due and owing to New York merchants. Thus, they pressed for conciliation with the South at all costs.

Even in 1860, decades after the United States had abolished the slave trade, ships launched from New York shipyards and financed by New York investors, though flying foreign flags and manned by foreign crews, carried slaves from Africa to Cuba, where the slave trade was still legal, yielding profits as high as $175,000 for a single voyage. Moreover, although New York State abolished slavery on July 4, 1827, the Tammany city government tolerated “blackbirders,” illegal slave importers who operated out of New York. Apparently, District Attorney James Roosevelt refused to prosecute them, believing their activities did not constitute piracy, although federal law defined it as such. Some blackbirders were professional bounty hunters searching for runaway slaves under the Fugitive Slave Act. A few even kidnapped free blacks for sale in the South. It is no wonder that Dan Emmett, a minstrel show composer, premiered “Dixie,” the Southern national anthem, in New York City on April 4, 1859.

The Mayor’s 1861 message argued, based on the effect of the secession crisis on New York City’s trade, the city fathers should anticipate the Union’s collapse with a policy of neutrality among the Northern and Southern states, noting that “With our aggrieved brethren of the Slave States we have friendly relations and a common sympathy.” He said New York City should strike for independence, “peaceably if we can, forcefully if we must.”

Wood was probably the first politician to show New York City provided far more tax revenue to the federal government than it received in public expenditure.

Finally, the Mayor suggested that New York, as a free city, financed through a nominal tariff on imported goods, could abolish all direct taxation on its citizens. Theodore Roosevelt noted in his History of the City of New York that the Common Council “received the message enthusiastically, and had it printed and circulated wholesale.”

While Wood may have contemplated the common good, he surely considered the vast possibilities inherent in running one’s own country. According to Luc Sante, the Common Council approved a plan for merging the three islands of Long, Manhattan and Staten into a new nation, to be called Tri-Insula. Three months later, after the rebels fired on Fort Sumter, the plan was quietly rescinded. The city survived despite more than $300 million in defaulted Southern trade debts and more than 30,000 suddenly unemployed workers. Within months, the Union’s demands for uniforms, rifles, artillery, and warships restored full employment.

Fernando Wood lost the mayoralty in 1861. Realizing the rise of William M. Tweed and his Ring to power was irresistible, he made peace. Wood was nominated to a safe congressional seat and other persons who had paid him approximately $100,000 to $200,000 for various appointments and nominations received them. Wood, aging gracefully, remained in Congress for the rest of his life. Although censured by the 40th Congress for “use of unparliamentary language” and defeated for the speakership in 1875, Wood became chairman of House Ways and Means in 1877. He died in 1881. Wood is buried in Trinity churchyard, at the head of Wall Street. As always, he is near the money.

New York Press, January 9, 2001

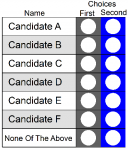

The option of voting for “None of these Candidates” or “None of the Above”—NOTA for short—enjoys support on both left and right. The Wall Street Journal endorsed NOTA in 1996, after Representative Wes Cooley of Oregon was re-nominated despite being exposed as both a fraud and a phony war hero. Although unopposed at the Republican primary, Cooley received only 23,000 votes while 31,000 voters cast blank ballots or various write-ins. The voters had no effective way to deny his re-nomination. This was two years after Representative Mel Reynolds of Illinois was re-elected unopposed following his post-primary indictment for raping a minor, possession of child pornography, and obstruction of justice. (Later convicted, forced to resign, and imprisoned, Reynolds was pardoned by President Clinton on his last day in office

The option of voting for “None of these Candidates” or “None of the Above”—NOTA for short—enjoys support on both left and right. The Wall Street Journal endorsed NOTA in 1996, after Representative Wes Cooley of Oregon was re-nominated despite being exposed as both a fraud and a phony war hero. Although unopposed at the Republican primary, Cooley received only 23,000 votes while 31,000 voters cast blank ballots or various write-ins. The voters had no effective way to deny his re-nomination. This was two years after Representative Mel Reynolds of Illinois was re-elected unopposed following his post-primary indictment for raping a minor, possession of child pornography, and obstruction of justice. (Later convicted, forced to resign, and imprisoned, Reynolds was pardoned by President Clinton on his last day in office