In his eight decades, Sadakichi Hartmann fried eggs with Walt Whitman, discussed verse with Stéphane Mallarmé, and drank with John Barrymore, who once described him as “a living freak presumably sired by Mephistopheles out of Madame Butterfly.”

Critic, poet, novelist, playwright, dancer, actor, and swaggering egotist, Hartmann might lift your watch (he was a superb amateur pickpocket) but his opinion was not for sale. Such a man evoked diverse opinions. Gertrude Stein said, “Sadakichi is singular, never plural.” Augustus Saint-Gaudens (whose equestrian statue of Sherman stands near the Plaza) wrote to him, “What you think of matters of art I consider of high value.” W.C. Fields said, “He is a no-good bum.”

Sadakichi Hartmann was born November 8, 1869 on Deshima Island, Nagasaki, Japan. His father was a German merchant, his mother Japanese. His father disowned him at fourteen, shipping him to a great-uncle in Philadelphia with three dollars in his pocket. Sadakichi observed, “Events like these are not apt to foster filial piety.”

While working at menial jobs, he educated himself at the Philadelphia Mercantile Library and published articles, poems, and short stories in Boston and New York newspapers. He crossed the Delaware to Camden to introduce himself to Walt Whitman. In 1887, he published a New York Herald article quoting Whitman’s opinions about other writers, which Whitman denounced for misquoting him. Undaunted, Sadakichi expanded the article to a pamphlet, Conversations with Walt Whitman. He later studied in Europe, meeting Liszt, Whistler, Mallarmé, and Verlaine, glimpsing Ibsen and exchanging letters with Anatole France. (He later sold France’s letter to an autograph hunter, exacting dinner for two at Maxim’s with two bottles of Pol Roger).

At twenty-three, he wrote his first play, Christ, drawn from Hartmann’s private non-historical and non-Biblical ideas, particularly a sexual relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene. When Christ, which he claimed had been compared to Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, was published in 1893, James Gibbons Huneker, the American aesthete, called it “the most daring of all decadent productions.” It was banned in Boston: the censors burned nearly every copy and jugged Sadakichi in the Charles Street Jail.

While working as a clerk for McKim, Mead & White, he described Stanford White’s drawings as “Rococo in excelsis. To be improved upon only by the pigeons, after the drawings become buildings.” White dispensed with his services. Thereafter, Sadakichi kept the pot boiling with hundreds of German-language essays for the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung.

In 1901, he published a two-volume History of American Art, which became a standard textbook. The History remains worth reading as an intelligent evaluation of American art’s first four centuries, marked by Hartmann’s insight into the modernist movements. His judgments are nearly clairvoyant: he analyzes the work of Thomas Eakins, Winslow Homer, and Albert Pinkham Ryder, all then nearly unknown. He also discusses Alfred Stieglitz as a photographer. Sadakichi was the first American critic to seriously discuss photography as an art form. Hartmann later contributed his most incisive writing to Stieglitz’s Camera Notes and Camera Work.

By 1906, he was famous, in Huneker’s words, as “the man with the Hokusai profile and broad Teutonic culture.” He stole a taxicab and somehow won acquittal in Jefferson Market Night Court by proving he did not know how to drive. When Moriz Rosenthal, a pianist who had studied under Liszt, enriched the Hungarian Rhapsodies by improvising a series of rapid scales during a Carnegie Hall concert, Sadakichi roared from the gallery, “Is this necessary?” As the ushers tossed him out, Hartmann shouted, “I am a man needed but not wanted!”

From 1907 to 1914, he lived intermittently at the Roycroft Colony, an artistic commune at East Aurora, New York, where he ghostwrote books for its founder, Elbert Hubbard, a soap salesman who had become rich by marrying the boss’ daughter. Hubbard had fallen in love with William Morris’s Kelmscott Press. Though utterly untalented, he saw himself as a Renaissance man just like Morris and attempted to recreate the Morris enterprises at Roycroft by spending money. Hubbard rationalized his ghostwritten books by arguing that all great art was collaboration.

In 1915, Sadakichi entered 58 Washington Square South, then known as Bruno’s Garret. Guido Bruno, its proprietor, was an exotically mustached émigré whose bluff, plausible manner and florid speech unsuccessfully concealed an instinct for the main chance. Bruno realized tourists would flock to gape at bohemians in their search for what some called Greenwich Thrillage. He promoted his Garret through flamboyant magazines, all featuring his name in the title: Bruno’s Weekly, Bruno’s Scrap Book, Bruno’s Review of Two Worlds, Bruno’s Bohemia, Bruno’s Chap Book, Bruno’s Review of Life, Love, and Literature and, simply, Bruno’s. In The Improper Bohemians, Allan Churchill described Bruno’s Garret as a layman’s dream of the artist’s life, where “artists’-model types of girls and hot-eyed young men who declared themselves poets, writers, and painters…behaved during working hours like artistic freaks,” declaiming verse and splattering canvases before tourists, herded from the Fifth Avenue bus, while Bruno collected admissions at the door.

The impresario proclaimed Sadakichi a genius. In Bruno’s Chap Book for June 1915, nine years before the Nouvelle Revue Française organized the first Western haiku competition, Sadakichi published “Tanka, Haikai: Fourteen Japanese Rhythms.” Five months later, Bruno proclaimed Sadakichi king of the Bohemians.

In 1916, Sadakichi went west. He revisited his first play’s subject in a novel, The Last Thirty Days of Christ, which envisioned Jesus as a mystic and philosopher misunderstood even by his disciples (anticipated Nikos Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ by a generation). It was praised by Ezra Pound and eulogized by Benjamin De Casseres as one of the most strikingly original works of American literature. He played the Court Magician in Douglas Fairbanks Sr.’s Arabian Nights fantasy The Thief of Bagdad (1924) for $250 in cash and a case of whiskey every week.

In 1938, Sadakichi moved to a shack on an Indian reservation in Banning, California. He still swaggered despite age, asthma, and a bad liver. (“My ailments are exceeded only by my debts.”) After Sadakichi collapsed on a bus, a doctor asked his symptoms. Hartmann replied, “I have symptoms of immortality.”

Though he still contributed to Art Digest and several European reviews, he generally lived on handouts cadged from admirers as tribute to his increasingly outrageous personality. John Barrymore, when asked why women still found Sadakichi, “this fugitive from an embalming table, so attractive,” replied, “Because he looks like a sick cat. Women are nuts about sick cats.”

Sadakichi’s friends in Los Angeles centered around the Bundy Drive studio of John Decker. They included Barrymore and Hearst editor Gene Fowler, then enjoying a wildly successful stint as a script doctor. This audience welcomed Sadakichi’s stories, all told with sly self-mockery and perfect timing. Fowler, according to his valentine, Minutes of the Last Meeting, he first spoke with Hartmann over the telephone in 1939. A few days later, while Fowler was at his office, a studio policeman said a crazy old man was asking for him. “When I told him he smelled of whisky,” the guard reported to Fowler, “he said I ought to be smelling his genius.”

Fowler went outside. The old man stood nearly six feet tall and weighed 132 pounds. Despite the heat, he wore a threadbare, baggy gray overcoat with an old sweat-stained fedora pushed back on his shock of gray hair, which had inspired Barrymore to nickname him the Gray Chrysanthemum.

He announced, “Where I come from and where I go doesn’t matter. For I am Sadakichi Hartmann.” (I’m condensing Fowler’s version here. Fowler extended his hand, saying, “Sadakichi, I am happy to know you.” The critic replied, “Is that remark a sample of your brilliance? You may live another century, Fowler, but you will never meet another son of the gods like me. You have something to drink?”

Fowler stammered, “As a matter of fact, I’m not drinking and—”

“What have your personal habits to do with my destiny?”

“I hadn’t expected a thirsty guest,” Fowler explained.

“You should always have something on hand to offset the stupidity of this place.” As Sadakichi helped himself to Fowler’s scotch, he said, “Be careful that you do not fall in love with your subject—in love with my wonderful character and genius. It will blind you, and your writing will suffer.”

Later, when an automobile accident interrupted Fowler’s work on the biography—it left him with “two split vertebrae, three cracked ribs, a skull injury, and wrenched knees. Otherwise I was as good as new”—Sadakichi complained that Fowler was malingering so as “to avoid becoming famous.” (“He suddenly realizes that I am much too big a subject for his limited talents.”)

Once, Fowler took Sadakichi to the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art. At the entrance, Sadakichi saw a wheelchair. He sat in it and motioned Fowler to push him about the gallery. He commented loudly on the paintings: van Eyck’s Virgin and Child (“Painted on his day off”) and a Rembrandt portrait of his wife Saskia (“Second-rate…he had begun to lose his mind when he painted it”). A curator bustled up, and Sadakichi asked him where the washroom was. The curator gave him directions. “Bring it to me,” Hartmann commanded.

Fowler recalled an attempt to have Hartmann examined by a physician. The doctor recommended that he be operated on for his hernia. Sadakichi resented this proposal—understandably, since in those days such ruptures could be repaired only by first removing the testicles. Decker urged the old man to bid the glands farewell. (“They have served their purpose and undoubtedly merit an honorable retirement.”) “Ghouls!” Sadakichi cried and turned his rage on the doctor. “Why don’t you men of medicine do something worthwhile instead of castrating a genius!” (Barrymore, weighing in, sustained Hartmann’s objections. “After all,” said he, “it is hard to cast aside comrades of happier times.”)

“Other people,” said Sadakichi, “talk and talk about dying. I’m doing it!” So he did, on November 21, 1944.

New York Press, May 1, 2001

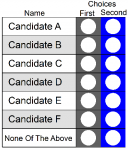

The option of voting for “None of these Candidates” or “None of the Above”—NOTA for short—enjoys support on both left and right. The Wall Street Journal endorsed NOTA in 1996, after Representative Wes Cooley of Oregon was re-nominated despite being exposed as both a fraud and a phony war hero. Although unopposed at the Republican primary, Cooley received only 23,000 votes while 31,000 voters cast blank ballots or various write-ins. The voters had no effective way to deny his re-nomination. This was two years after Representative Mel Reynolds of Illinois was re-elected unopposed following his post-primary indictment for raping a minor, possession of child pornography, and obstruction of justice. (Later convicted, forced to resign, and imprisoned, Reynolds was pardoned by President Clinton on his last day in office

The option of voting for “None of these Candidates” or “None of the Above”—NOTA for short—enjoys support on both left and right. The Wall Street Journal endorsed NOTA in 1996, after Representative Wes Cooley of Oregon was re-nominated despite being exposed as both a fraud and a phony war hero. Although unopposed at the Republican primary, Cooley received only 23,000 votes while 31,000 voters cast blank ballots or various write-ins. The voters had no effective way to deny his re-nomination. This was two years after Representative Mel Reynolds of Illinois was re-elected unopposed following his post-primary indictment for raping a minor, possession of child pornography, and obstruction of justice. (Later convicted, forced to resign, and imprisoned, Reynolds was pardoned by President Clinton on his last day in office